To catch up on earlier chapters of this story, click on the links below:

One reason I walked from Nottingham to Newcastle was to learn about the places between my two hometowns that we bypass when driving down the motorway: a kind of cartographical pilgrimage, as I described in Part 1.

As I set off, my head was buzzing with historical fiction because I’d just read The Last Kingdom by Bernard Cornwell, which begins with the hero, Uhtred of Bebbanburg, effectively making my journey in reverse: riding with his father from Northumberland to defend York, where he is taken captive by the Vikings, and later rowing up the River Trent with his captors to attack Mercia. If true, their boat would have passed within a whisker of Burton Joyce, the village where I grew up in the Trent Valley. Uhtred narrates as follows:

“Rorik and I sat in the prow with his grandfather, Ravin, and our job was to tell the old man everything we could see, which was very little other than flowers, trees, reeds, waterfowl and the signs of trout rising to mayfly. ‘Mercia is frightened of us,’ Ravn said. He lifted his white, blind eyes to the oncoming air, ‘and they are right to be frightened. We are warriors.’

We ended the voyage at a town called Snotengaham [Nottingham], which means home of Snot’s people, and it was a much greater place than Gegnesburgh [Gainsborough], but its garrison had fled and those people who remained welcomed the Danes with piles of food and heaps of silver.”

So, there we have it; I am officially a Snot, a moniker that always caused much hilarity in school history lessons! But what I didn’t learn at school was that the Vikings invaded Nottingham in 868, so I was transfixed reading The Last Kingdom and searched for more evidence of that cataclysm on my journey north.

The search didn’t take long.

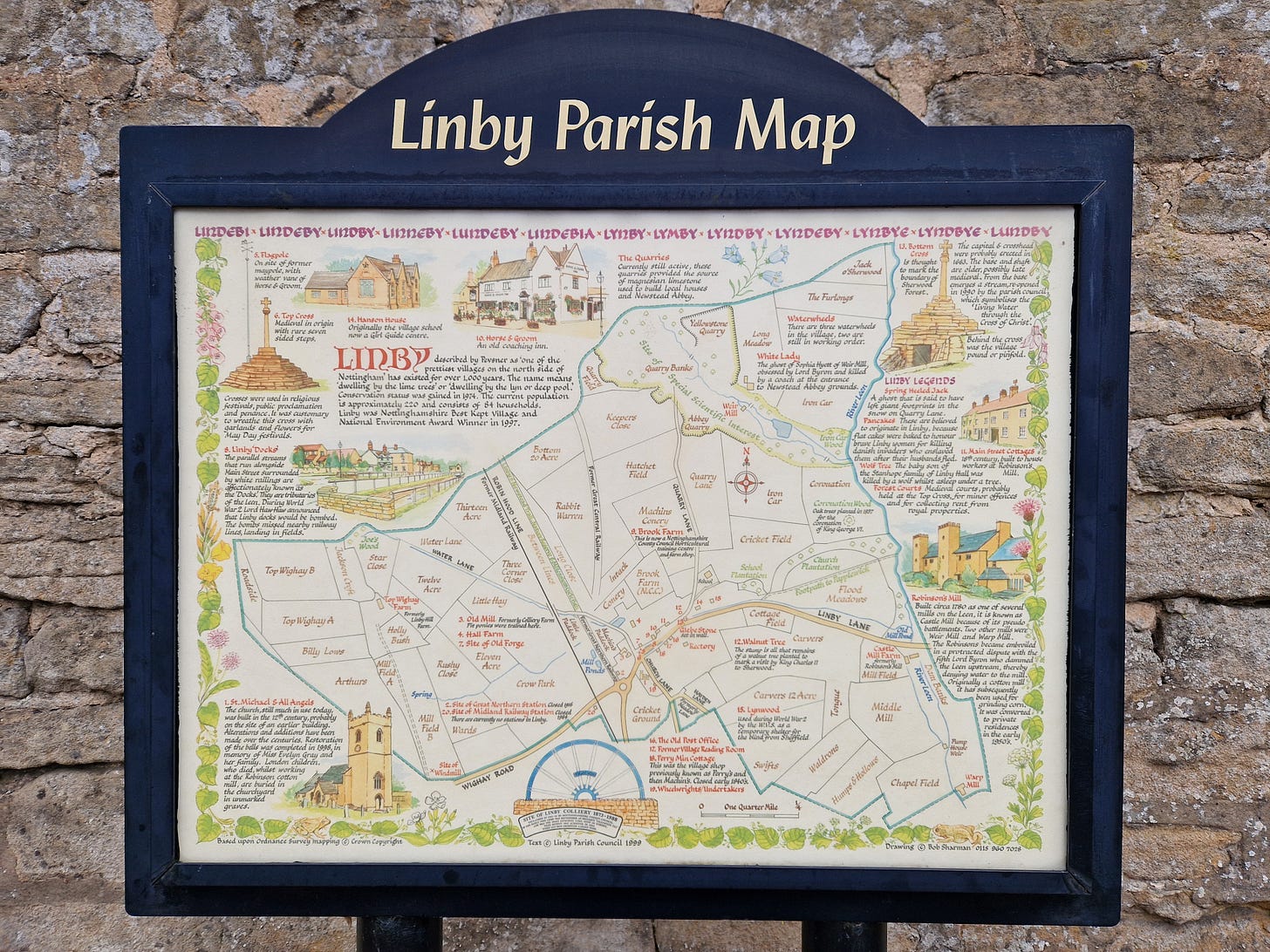

I stopped for lunch on my first day in the charming village of Linby, a sure contender for the ‘Best Kept Village Competition’ with its profusion of hanging baskets, market cross, stream and pub.

No sign of marauding Vikings, but etymologists will know that the suffix ‘-by’ comes from the Viking- word for farmstead, village or settlement. But the story of Viking Linby doesn’t end there. A beautifully illustrated Parish Map claims that pancakes originated in Linby because ‘flat cakes’ were baked to honour the local women for killing Danish invaders who enslaved them after their husbands fled. Sadly, Bernard Cornwell missed that juicy slice of local folklore. However, the café where I ate, Brooke Farm, capitalises on this legend by serving its famous ‘stack of pancakes’, although the lady who served me couldn’t confirm the ferocity of the smartly dressed women, with their patterned blouses and hefty handbags, who made up the lion’s share of the clientele that lunchtime. I sat in the corner to charge my phone whilst listening to the steady hubbub of conversation and clink of teacups.

As I walked further north, I entertained myself by ticking off more Viking place names along my route: Budby, Ranby and Lound in Nottinghamshire, followed by Osgodby, Bishopthorpe and Oswaldkirk in Yorkshire (-bys, -lounds, -thorpes, and -kirks). I also stumbled across an unexpected Viking-inspired find in a churchyard just north of Stockton: a long rectangular stone with tile-like markings carved along its top, known as a Hogback Grave Cover, made by Norse settlers to resemble the roof of a Scandinavian longhouse. However, this one is thought to be a replica made in the 12th century.

Perhaps the most curious place I discovered was the Isle of Axholme in North Lincolnshire. I knew I had to visit when I read the words ‘ISLE OF AXHOLME’ printed in block capitals on my map, lurking between Gainsborough and Goole. An island in the middle of the land? What’s more, no one I knew had heard of the place.

My first view of the so-called ‘Isle’ was from the ancient village of Gringley on the Hill, an outpost in northeast Nottinghamshire. After climbing up to Beacon Hill, thought to be a bronze age burial mound and the highest point for miles around at a heady 82 meters, I had an uninterrupted view over pancake flat farmland, and if it hadn’t been hazy, I might have been able to see all the way to Goole. I stopped at a house to ask a man if I could fill up my water bottles from his outside tap. He agreed, and as I was doing so, he told me about the area, “The whole plain was once a large marsh surrounded by rivers, and the people used to fish for eels.” I left him admiring the view from his eyrie on the hill and descended to my prickly campsite on the Chesterfield Canal.

As I walked north over the next few days I learned more about the Isle’s turbulent history from information boards beside the path. In the 1620s, the marsh was drained by the Dutch engineer Cornelius Vermuyden on behalf of Charles I. If you think ‘Cornelius Vermuyden’ sounds like the name of a pantomime villain, you wouldn’t be far off the mark because he was vilified by those eel-eating Isleonians who lost their livelihoods fishing and wildfowling in the nature-rich marshland as it dried up. A Stuart-era example of environmental and cultural destruction on British soil. The King gave Vermuyden and his backers a third of the reclaimed land, he kept a third, and one-third (the poorest part) was left to the natives.

This story of land-grabbing would have reverberated with the medieval commoners of Sherwood Forest, except for them, the aristocracy created a Ducal playground, still known as ‘The Dukeries’ today, where the punishment for catching a hare or hind to feed your family was having a hand chopped off, being blinded in both eyes, or even death: tyrannical ‘Forst Law’. To my mind, it was from this oppression that the legend of Robin Hood grew (see Part 1). Perhaps he was more of a cause than a person? The age-old fight of the commoner for land rights.

In the Isle of Axholme, drainage workers were attacked, sluices broken, and opposition to the drainage persisted for 80 years with violence on both sides. According to accounts, it was like the ‘Wild West’ of America in the 19th century, but in this case, the ‘Wild East’ of England in the 17th. Eventually, the Isleonians sided with the Parliamentarians in the civil war because the project was sponsored by the crown, so in 1649, they got their revenge when Charles I was beheaded.

As I walked, I took in the landscape: fields ironed flat; drainage ditches running ruler-straight to the horizon like a lesson in perspective; the odd vertical structure – a windmill, a turbine, a lonely tree – standing watch. Coincidentally, I was reading A Flat Place by Noreen Masood, a reflection on flat landscapes such as Orford Ness and Morecambe Bay, and I agreed with her thesis that while such places lack the dramatic mountain scenery, they can be strangely calming. The view hardly changes throughout the day. Walking lacks drama and becomes more of a meditation.

In the middle of the Isle of Axholme, I arrived at a village called Haxey, where I saw a peculiar object on the village green. Jutting out from a block of wood was a baton, about three feet long. As I was attempting to read a hand-carved sign above, a woman stopped to tell me that the object is used in a festival on 6th January each year called ‘The Haxey Hood’. Villagers from all around form a scrum and attempt to push the baton to their favourite pub, which, judging by a video on YouTube, is followed by lots of drinking. The rules of the game are written on the sign in the local dialect: “Oose agen oose toon agen toon, if a man meets a man knok ‘im doon, but doan’t ot im”, which the woman kindly translated for me as: ‘House against house, town against town, if a man meets a man knock him down, but don’t hit him’.

The game is said to have begun in the 14th century when Lady Mowbray of Haxey Manor was out riding; her silk hood blew away, and thirteen farm workers rushed across the fields to retrieve it (the commoners must have been more reverential in those days). She was so delighted that her hood had been found that she set up a yearly reenactment.

I tried to place the dialect, wondering if it was a cross between Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire, but, to me, it had more of Gordie twang, with the words ‘oose’ and ‘toon’.

Before arriving in Goole, I got a taste of what the Isle of Axholme might have felt like pre-drainage whilst camping on the remote and uninhabited ‘Crowle Wastes’, as it’s marked on the map. As I wrote in Part 3, it was a challenge to find anywhere secluded to camp in such an open landscape, so, I took a detour a few miles north-west from Crowle towards what is now a nature reserve, but until recently was exploited for peat extraction. As I crossed the prosaically named ‘Moor Middle Drain’, the large open fields transformed into a messy mix of heather, bracken and reeds. Starlings were replaced with geese flying low between ponds, and a barn owl hunted around my tent at dusk. Suddenly, there were flies, spiders and other creepy crawlies probing the flysheet of my tent. It was like stepping through a looking glass into a world of wildlife.

Two days walk north of Crowle, I came face to face with the majestic façade of York Minster after loosely tracing the River Ouse (a Viking highway) upstream from Goole. After nearly a week of vagabonding through field and forest, I was wonderstruck beholding this limestone megalith. I’ve visited York numerous times over the years for business meetings, flitting in and out on the train, but arriving on foot left a much deeper impression on me. Before modern urban sprawl, the city must have risen from the surrounding countryside like a giant geological mesa ringed by its two-mile-long city walls. I enjoyed a well-earned day off in York, staying with my godson, Nathanial, who is at university there. First, he gave me a tour of his campus before we circumnavigated the walls with a troupe of other tourists.

Although most of the walls date from the 13th and 14th centuries, I was interested to discover that one part, the lower half of the Multangular Tower (with ten sides) overlooking the Museum Gardens, remains from Roman times. The other snippet of information that caught my attention was a sign on an information board by Baile Hill that says the castle was built following a rebellion by York’s Anglo-Scandinavian elite in 1069, just after the Norman Conquest. “William’s response was so forcible it became known as the ‘Harrying of the North’. Much of the north of England was systematically ravaged. William allegedly ordered his troops to slaughter every living thing between York and Durham.” A medieval genocide, perhaps planned from William’s powerbase in Nottingham Castle, at the southern end of ‘THE KING’S WAY’, which I’d just walked.

Not all my observations on Place were about ancient history. A more recent activity, coal mining, left the strongest impression on me. Indeed, my route from Nottingham to Newcastle could be named ‘The Miner’s Way’. Everywhere I went, I passed decaying industrial relics: the shattered landscape that was once Rufford Colliery but is now a vast remediation scheme of tyre-gouged clay, bald pit heaps, and burnt-out cars; a pair of headstock winding towers at Clipstone, still standing against all the odds, facing each other like steel skeletons; a giant mining drill on the path to York, once used in the Selby super-pit, with a white rose painted in the middle; and after a brief gap crossing the rolling hills in North Yorkshire, a string of Country Parks in County Durham, each with their own grassy pit heap and memorial winding wheel: Hetton, Herrington, Washington. On my return home, with these visions fresh in my mind, I watched the gritty TV drama Sherwood on my return. The legacy of pit closures in the 1980s still bites deep, and it struck me that my two hometowns are umbilically linked by coal.

If you’re beginning to get the impression that my whole journey comprised of flat farmland and industrial wastes, there was a more picturesque stage of around 50 miles between York and the River Tees, where I passed through a more typical backpacking landscape of hills, moorland and market towns. Here, I enjoyed the best views of the trip (as well as the most expensive lunches), with one particularly memorable panorama on the Cleveland Way that runs along the western edge of the North Yorkshire Moors. I arrived on the edge of the escarpment mid-afternoon just as a giant raincloud burst to the east over the Vale of Mowbray like a galactic spaceship probing the land below with a thousand tentacles illuminated with crepuscular rays. As it passed, the patchwork of fields below turned as dark as night, only to spring back to emerald-green a few minutes later. That evening, I pitched my tent on the edge of the path and watched a spectacular sunset as the temperature plummeted.

I passed several castles in North Yorkshire, including a ruin in Sherriff Hutton that dominates the view for miles around but is on private property and closed to the public, Helmsley Castle that stands guard on a hill above this ever-popular market town, and most intriguingly a stone ruin almost wholly hidden from view, near the village of Swainby. The place was unattended, and I freely wandered through the wooden portcullis to explore the shell-like structure with its hollowed-out chimney breasts, gaping windows and secret chambers. Looking it up on the internet now, I can see the place is called Whorlton Castle, and the area I explored was the gatehouse, the only surviving part.

One of the last landmarks I visited before arriving back in Newcastle was the Penshaw Monument, which had become like a homing beacon in my mind. The monument, a 19th-century folly built to resemble a Greek temple, can be seen clearly from the top of a hill close to my house in Newcastle, 10 miles to the north. The Lambton Worm, my favourite local poem, tells the story of a fearful dragon-like creature that ate children and could wrap itself seven times around Penshaw Hill before it was slain by the ‘heroic’ local landowner, Sir John. It was probably written as shameless propaganda to curry favour in the eyes of Lambton’s tenants, but it has a canny ring to it, and I attempted to memorise the words as I walked:

Whisht! Lads, haad yor gobs, An Aa'll tell ye's aall an aaful story Whisht! Lads, haad yor gobs, An' Aa'll tell ye 'boot the worm.

But the worm got fat an' growed and' growed An' growed an aaful size; He'd greet big teeth, a greet big gob, An' GREET BIG GOGGLE EYES! An' when at neets he craaled aboot Te pick up bits o' news, If he felt dry upon the road, He milked a dozen coos.

I ate my breakfast on the monument's stone base, watching the sunrise to the east over the North Sea on a blisteringly clear morning, except for a wispy film of mist lying over the fields below. To the north, Newcastle called to me across the River Tyne, as well as the outline of the Cheviot Hills looming on the horizon beyond. My own backyard.

In conclusion, I’m happy to say that I achieved my aim of linking all the places on the map between Nottingham and Newcastle with an unbroken chain of footprints and memories, exploding my mental map. Lying in bed at night, I can close my eyes and visualise nearly every turn in the path, village, castle, and campsite. Mission accomplished. Except that there is always another story to tell.

CONTINUE READING: PART 5

NB: Unfortunately, many places between Nottingham and Newcastle didn’t make the final cut, and telling all the tales of the places I passed would have meant writing a book on the history of northern England. So apologies to Newstead Abbey, Edwinstowe, Clumber, Misterton, Epworth, Google, Drax, Osgodby, Bishopthorpe, Strensall, Sheriff Hutton, Osmotherley, Rudby, Stockton, Thorpe Thewles, Wingate, Shotton Colliery, and Washington.