June 2024

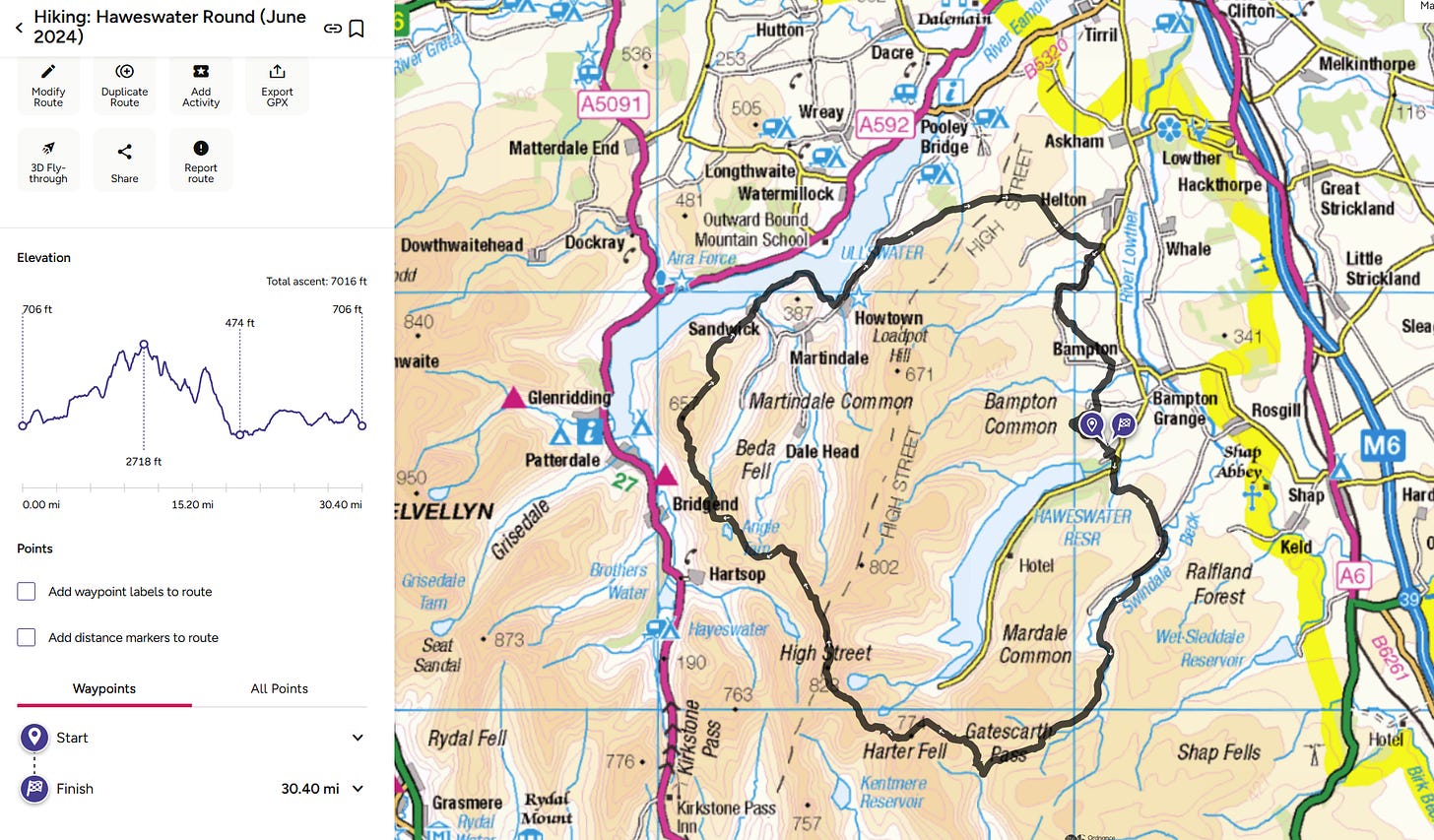

After my last wet and cloudy backpacking trip around Langdale in March (read here), I’d been itching to get back out in my tent in better conditions, so took advantage of a weather window after what seemed like months of rain. I only had a few days – squeezed in between jobs – so planned a route in the Lake District’s Far Eastern Fells, closest to where I live in Newcastle. Top of my list was visiting Swindale to see the results of the Wild Haweswater project to re-wiggle the river and hopefully immerse myself in nature. From there, I would traverse across the fells to Ullswater, with a camp at the summit of High Street, before looping back via the stone circle on Askham Fell: around thirty miles of mountains, meadows and bird song.

Link to GPX on OS maps here.

I parked the car in the reservoir village of Burnbanks and made a generous donation to their red squirrel fund. There was a sign saying ‘No overnight stays’, so before setting off, I knocked on the door of one of the cottages to seek permission, which was kindly given. By coincidence, I spoke to a man who rebuilt the whole village about 30 years ago. Residents clearly take pride in their community because I also met a woman watering a begonia in the bright red telephone box.

Cuckoos and redstarts

I made slow progress up to Swindale because I kept stopping to listen to a calling cuckoo echoing across the heavily wooded Naddle Valley: the sound of summer; also a sign of a healthy environment with plenty of songbird nests to infiltrate. I kept my eyes peeled for those grey, swept-back wings and thought I glimpsed one swooping low over the heather.

I ate my lunch in the heart of Swindale, where I had a slantwise view over the river, which curved graciously through a buttercup and clover meadow circled by mewing buzzards. The meadow itself was fenced off, so I couldn’t inspect the new habitat for riffle sections or gravel banks but traced the beck with my eye, which is now said to be 180 meters longer than it was in 2016. You can see before and after shots on the BBC website here: How ‘rewiggling' Swindale Beck brought its fish back - BBC News.

While I was watching the river, a bird called from a stone wall. At first, I assumed it was a stonechat, but it was taller, slimmer and arguably more handsome. I had an idea of the identification but confirmed it by recording its call on the Merlin bird app: an upward sweeeeep rather than a harsh chat. A redstart, or more descriptively, 'firetail'. On the audio recording graph, every bird call makes a unique pattern: the redstart is an upward curve; skylarks make seemingly random scratches; blackbirds are spiky mountain peaks. The cuckoo creates two distinct towers, like pylons: the first tall and thin, the second short and fat.

There was yet more wildlife at the head of the valley, with pink flowering orchids nestled amongst the grass and spotted flycatchers darting about the rocks of a tree-lined waterfall. Upstream of the waterfall, lowland Swindale becomes upland Mosedale. It's a dramatic turn of events in the life of this peaceful Beck overlooked by Selside Pike. I climbed Selside Pike ten years ago when I was finishing off all the Lakeland fells on the run-up to my 40th birthday. It was December, and I walked in thick clouds, so I never got to see the pre-wiggled river in Swindale. However, Wainwright had a soft spot for the area, writing in The Far Eastern Fells: 'One of the lesser-known fells is Selside Pike on the eastern fringe of the district, commanding the head of the sky and beautiful little valley of Swindale… Fifty years ago engineers took over the valley with the idea of building a reservoir; now they are gone, mercifully leaving the valley as they found It.’ I hope he would have appreciated the rewilding project more than he did the Haweswater Reservoir.

Tents and bothies

Mosedale was a complete contrast to Swindale: miles of featureless grassland. However, I did spot the herd of resident red deer on the far side of the valley, looking very much at home and around 30-strong. The only landmark in Mosedale is a sizable, whitewashed cottage that, at first, I thought might be a hunting lodge but turned out to be a bothy. It was deserted when I passed and, although well-maintained, had a zombie post-apocalyptic vibe. I imagine that in the company of fellow hillwalkers when the fire is lit on a winter's night, it has an altogether more welcoming atmosphere. For a video tour, click here.

After a promising start to the day, it had clouded over, and I dropped down to a soggy valley called Brownhowe Bottom before pulling up a steep slope to Harter Fell. Here, I got my first view of Haweswater, which I would be circling on this walk, nestled in between two green ridges. At the head of Haweswater is a tarn called Small Water where, with the aid of binoculars, I could make out a gaggle of luminous green tents and a party of wetsuit-clad humanoids clambering up the gully.

I paused for an afternoon break at the Nan Bield Pass overlooking Kentmere Reservoir and pulled on my buff and woolly hat for warmth. From there, I admired the ridge of three hills on the horizon that point due south to Kentmere: Froswick, Yoke and the distinctively shaped Ill Bell.

I thought I might camp on the far side of High Street at Angle Tarn, but on reaching the runway-like summit, although it was cold, there was not a breath of wind. It seemed like too good an opportunity to miss, so as I always do, I padded backwards and forwards, assessing every inch of land for the perfect spot: flat, short grass, sheltered behind the wall. On several occasions, I've done all this only to crawl into my sleeping back after dinner to find a hitherto undiscovered rock jutting into my back, or apparently, flat land has mysteriously become a slope. That evening, I got it just right. I cooked dinner using the wall for shelter and support, watched a glowing, cloudy sunset over Helvellyn to the west, and slept soundly.

Warming up and cooling down

I love waking up on a mountain first thing in the morning. At first, you have the whole place to yourself, except for sheep and, on that morning, skylarks. You boil water on your stove, lounging in your sleeping bag, watching the steam rise. You drink tea and admire the view. You break camp and walk downhill. After a while, with a spring in your step, you pass the first climbers puffing up the slope, who look at you askance, like salmon to fresh water, wondering if you have been walking all night. It was the same on that day, and later that morning, around Angle Tarn, I passed a long string of hikers coming toward me on the Coast-to-Coast Walk.

But first, I ambled north along High Street in splendid isolation, pausing to admire the majestic U-shaped valley of Riggindale funnelling down to Haweswater. The sun transformed the meandering beck into a silver rivulet set in green velvet. I traced the stream down the valley to the reservoir and then back, returning up the dragon-back ridge that guards the valley to the right. The ridge is marked with a trio of animal names on the map: Swine Crag, Heron Crag (not named after the grey heron, but rather erne or white-tailed eagle), and Eagle Crag. The last, Eagle Crag, is a cartographical eulogy because eagles no longer soar here. But once, I beheld that solitary golden eagle that lived alone for twelve years like Puff the Magic Dragon until it faded into the mists of time in 2015. I hope I will see eagles return to Haweswater in my lifetime. This blog on the Wild Haweswater website by Lee Schofield ends with a positive note, so fingers crossed: Holes in the map, part 4: Eagles - Wild Haweswater.

By the time I reached Angle Tarn, the crowning glory of Lakeland tarns, the June sun was beginning to warm the Baltic air. Seeing that a couple were already in the water gave me the courage to follow their example. I walked down the small promontory to the beach, pulled out my super lightweight Lightload Beach Towel and got changed. I called across to the other intrepid swimmers who were now getting changed and asked them to excuse any cries of agony as I went in. 'That’s all part of the fun’, came the jovial reply. The water was warmer than expected, and I swam across to the island before and lolling around on my back, feeling weightless and relaxed.

But the cold hit me when I got out. I felt exhilarated, but also befuddled, and fumbled with my clothes. As I set off, I realised I wasn’t wearing my wedding ring. I stumbled back to the shore and traced a path back to my rucksack. Shore, rucksack. Shore, rucksack. I felt sick and wasn’t looking forward to relaying the news to Tracy. Usually, I leave it at home for this very reason. Did it slip off in the water? No, I remember taking it off my puffy fingers and securing it on my watch strap as usual. I’d put my watch back on, so it must have fallen off when I dressed. I looked down around the base of my pack. Nothing. I moved my foot to one side and saw a glint of gold swashed into the mud. I pulled it out, and the relief and joy flowed through me. I felt like I’d found a Viking hoard. I continued my journey over Angletarn Pikes in a more reflective mood.

At Boredale Hause, I had a choice of whether to veer left and follow the east shore of Ullswater or climb up and over Place Fell. A hill I probably last climbed when I was three in Wellington boots. But as I ate lunch, the long white ribbon of a path up the slope called to me, so my fate was determined. I reached the summit with its sturdy rock triangulation column and admired a stunning view north over the top end of Ullswater to Scotland. Again, I was hit by cold blasts of wind and pulled on more layers.

After lunch, I was tired and longing for coffee. I checked my watch and figured I could just make the café at Howtown by closing time, so skirted Hallin Fell and arrived at the bonny Howtown Hotel just after the lady serving had turned off the coffee machine. ‘But I can make you a cafetiere’, she helpfully suggested after registering my dismay. ‘Thank you’, I replied, ‘I like it strong’. I retired to the hotel garden with a tray laden with coffee, water, and cake and sat for over an hour rehydrating and admiring the immaculate garden, with swallows swooping over the adjacent meadow. It was a bucolic spot nestled amongst the hills and bathed in afternoon sunshine. It was difficult to tear myself away, but I eventually returned my tray to the servery and continued south.

Druids and fell-runners

I was wary about where to camp on my second night because I would be closer to civilisation, and after a delightful few miles trotting along a terrace path that overlooks Ullswater, I arrived on Askham Fell. I climbed up a wide track to gain some height and a view, but the hillside was swathed in bracken and uneven. As I was pacing about, I struck up a conversation with a man from Penrith walking his dog. He recommended that I camp in a stone circle marked ‘The Cockpit’ on the map, telling me it was quiet and often used by outward-bound groups for camping. After thanking him for the advice, I plodded back down the hill and found the spot. It was perfect. The stones were only a foot or two high, so it certainly wasn’t Stonehenge, but the ground was as flat as a pancake with cropped grass. As I pitched my tent, I wondered if I would encounter ancient deities sleeping on hallowed ground. I spent much of the evening imagining the people who had placed the stones and gathered there. I half-hoped I would wake at midnight to the sound of medieval knights on horseback or chanting druids, but the most activity I encountered was a group of about thirty multicoloured fell runners ending their evening meet at the stones while I cooked dinner. They were all milling about, so to break the ice, I cheerily offered them a share of my chilli bean stew and got a good laugh from the crowd as someone announced they would have one bean each. After they dispersed, I enjoyed an atmospheric sunset and one of the best night’s sleep in my tent.

Footpaths and access land

The following morning, after being woken up by a symphony of skylarks (video here) – an ever-present soundtrack to this trip – I walked south, roughly parallel with the River Lowther, along country lanes brimming with flowers and a patchwork of infrequently visited access land. (Access land makes up most of the 8% of land in England where there is a right to roam. See Who Owns England, by Guy Shrubsole). At Cockle Hill, I was treated to a surprisingly good view of a barn owl hunting low over rough ground. Back and forth, it silently flapped in the morning sunshine until it suddenly twisted and plummeted on breakfast. Video here.

Next, I negotiated a frustrating section of overgrown footpaths where many signposts were mysteriously broken or missing before reaching ‘The Howes’ near Bampton. Here, I set myself a challenge of traversing two more patches of access land to avoid a detour. ‘The Howes’ and ‘Yews Mire’ are connected, but only by a neck of land about 100 meters wide bisected by a stream. It took some finding, pushing through large stands of spikey gorse and a soggy bog, but I arrived hot, sweaty and jubilant on the far side near Aika Hill as if I’d crossed the Sahara. I would have made Mr Shrubsole proud!

Full circle

After that, all that remained was to wind down a graceful hillside swathed in bracken back to the wooded village of Burnbanks. My car sat in the small car park safe and sound. The cuckoo still called, and the phone box shone red. By coincidence, the resident I asked about leaving the car for two nights was walking his dog down the street, so I told him I’d arrived safely, and we chatted about my route.

It had been a grand walk in the Far Eastern Fells.

A lovely part of the Lakes and definitely one less trodden. I’ve been following the Rewilding Haweswater project for some time and been especially interested in the use of cattle. The jury are still out with me on that tactic…